Academic Writing with Artificial Intelligence in Neurosurgery

Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming academic writing, particularly in specialized fields such as neurosurgery. Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT offer practical benefits including improved readability, support for non-native English speakers, assistance in drafting abstracts and introductions, and tools for visualizing data and organizing results. Recent studies (Fauziah et al., Schneider et al., Akgun et al., Nabata et al.) demonstrate that AI-generated content often matches or exceeds human-authored texts in surface-level quality and readability, though it may lack depth, originality, and clinical nuance. Despite their potential, AI tools raise ethical concerns regarding authorship attribution, misinformation, and data privacy, especially in contexts involving patient information. Studies reveal that human reviewers frequently fail to distinguish between AI- and human-generated writing and sometimes prefer AI outputs for their clarity. The growing presence of AI in neurosurgical publishing underscores the need for transparency, ethical guidelines, and integration policies. While AI cannot replace expert insight, it serves as a powerful augmentation tool that—when used responsibly—enhances efficiency, clarity, and accessibility in scientific communication.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence · Large Language Models · Neurosurgery · Academic Writing · Scientific Publishing · Authorship Ethics · Readability · ChatGPT

Introduction

Academic writing plays a central role in the dissemination of knowledge, advancement of clinical practice, and development of evidence-based medicine in neurosurgery. However, the increasing demands of research productivity, publication pressure, and the need for high-quality English prose—especially among non-native speakers—pose significant challenges for researchers. In this evolving landscape, Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, is emerging as a powerful tool to assist in the generation, refinement, and structuring of academic content.

AI-based writing assistants offer a range of capabilities, from correcting grammar and enhancing clarity to generating full drafts of scientific abstracts, introductions, and technical reports. Their integration into the academic workflow can streamline manuscript preparation, support literature review processes, and improve accessibility and readability of complex scientific information. This is especially relevant in neurosurgery, where the high technical demands of the discipline often intersect with the need for precise and nuanced communication.

Despite these advantages, the use of AI in academic writing raises critical questions around originality, accuracy, authorship attribution, and ethical use. Studies have shown that AI-generated texts can be indistinguishable from human-authored ones and are often preferred for their readability, yet concerns remain regarding their depth of analysis, clinical judgment, and factual reliability.

This article explores the opportunities and limitations of AI in neurosurgical academic writing, drawing upon recent comparative studies, including works by Fauziah et al., Schneider et al., Akgun et al., and Nabata et al. Through a synthesis of current evidence and ethical considerations, we aim to provide a balanced perspective on how AI tools can be responsibly integrated into the scientific publishing process—complementing rather than replacing human expertise.

Materials and Methods

This article adopts a narrative review approach to examine the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly large language models (LLMs), in academic writing within the field of neurosurgery. The objective is to synthesize recent literature, highlight emerging trends, and critically assess both the potential and limitations of AI-assisted writing tools in scientific publishing.

To inform this analysis, we conducted a targeted literature search in PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for studies published between January 2023 and March 2025. Search terms included combinations of “artificial intelligence”, “large language models”, “ChatGPT”, “academic writing”, “scientific publishing”, “neurosurgery”, and “authorship ethics”. Priority was given to peer-reviewed studies that directly compared AI-generated and human-authored texts, assessed readability metrics, or explored the ethical and practical implications of AI use in manuscript preparation.

Four key studies were selected for in-depth analysis:

Fauziah et al. (2025) – Comparative readability and perception of AI vs. human-written neurosurgery articles Schneider et al. (2025) – Detection and prevalence of AI-generated content in neurosurgical journals Akgun et al. (2025) – Expert evaluation of AI-generated vs. human-authored full-length neurosurgery manuscripts Nabata et al. (2025) – Accuracy of human reviewers in identifying AI-generated scientific abstracts In addition to these core studies, supplemental literature was reviewed to contextualize findings within broader discussions on AI ethics, transparency in authorship, and academic integrity. Where relevant, observations from clinical and educational use cases of AI-assisted writing tools were integrated to provide practical insights for neurosurgeons, trainees, and academic institutions.

No patient data were used in this review. The analysis is based solely on publicly available literature and does not require ethics committee approval.

Results

Four primary studies were identified that directly investigated the role and impact of AI-generated content in neurosurgical academic writing. These studies collectively highlight a shift toward the integration of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT in various stages of manuscript development, from abstract drafting to full-length article generation.

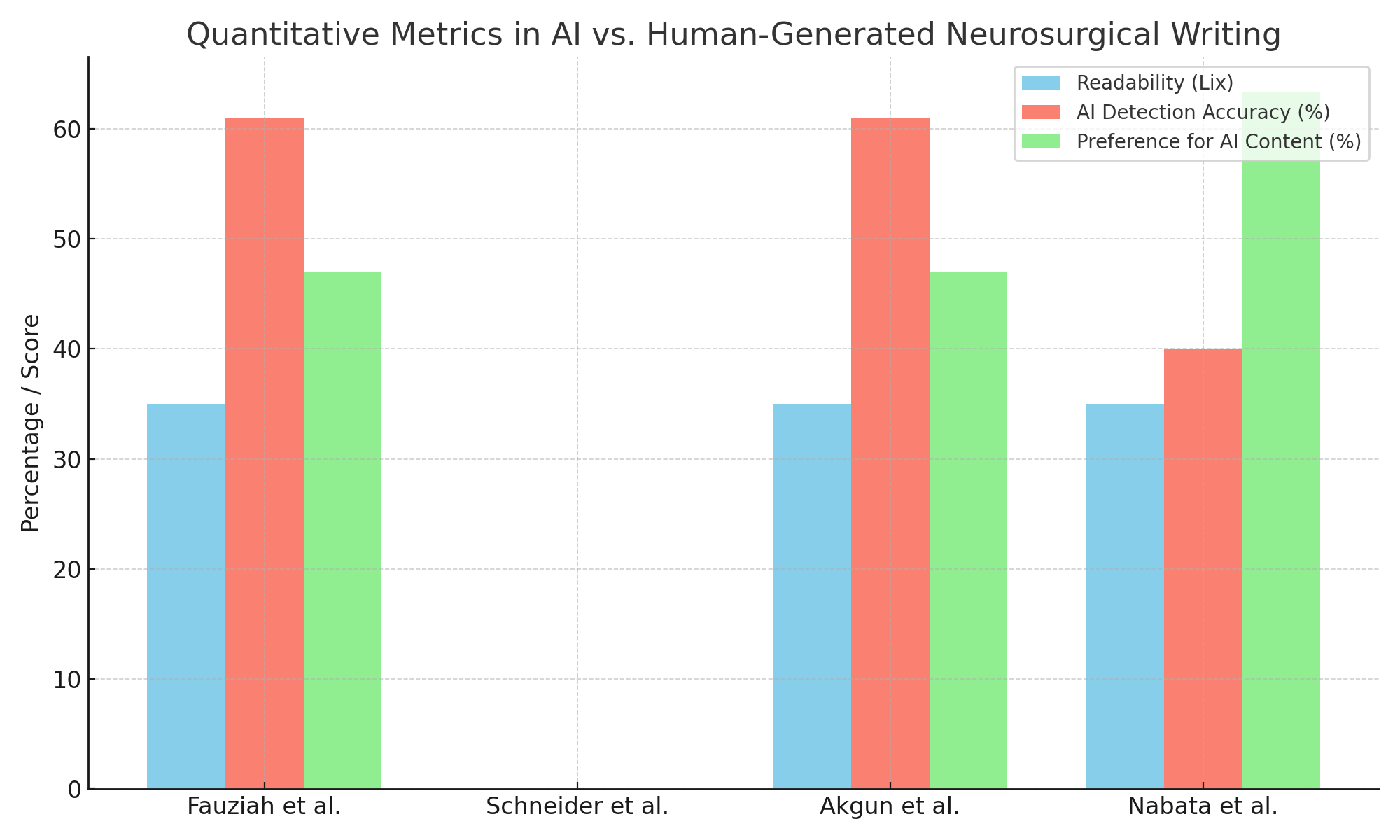

Readability and Preference: Both Fauziah et al. and Akgun et al. reported higher readability scores for AI-generated texts compared to those written by humans. In both studies, participants showed similar or even higher preference for AI-generated content (47–63%), despite modest accuracy in detecting AI authorship (around 61%).

Prevalence and Detection: Schneider et al. found that approximately 20% of recent neurosurgical publications contained sections likely generated by AI, especially in the methods and abstract sections. However, after removing abstracts from the analysis, the statistical significance of section-specific AI prevalence was lost, suggesting inherent formatting biases in detection tools.

Reviewer Discrimination: Nabata et al. demonstrated that most surgical faculty and trainees could not reliably distinguish between original and AI-generated abstracts. Surprisingly, a significant portion (63.4%) preferred the AI-written abstract, emphasizing the persuasive clarity and structure of LLM outputs.

Ethical Implications: All four studies underline the urgent need for transparency in AI use. While the benefits of AI are clear—particularly in enhancing clarity and reducing language barriers—issues surrounding factual accuracy, authorship credit, and ethical oversight remain unresolved.

| Study | Study Type | Main Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fauziah et al. (2025) | Comparative analysis of AI vs. human-written articles | AI-generated texts had higher readability but less depth; 61% accuracy in identifying AI authorship | AI improves accessibility but lacks clinical nuance; requires expert oversight |

| Schneider et al. (2025) | Prevalence study using AI-detection tools | 20% of neurosurgical manuscripts contained AI-generated content; especially in abstracts and methods | AI detection is increasingly unreliable; ethical disclosure and transparency are essential |

| Akgun et al. (2025) | Expert evaluation of article quality | ChatGPT-generated articles had higher readability and comparable quality; 47% preferred AI, 44% human | AI can assist in drafting; fact-checking and clinical validation are critical |

| Nabata et al. (2025) | Observational study with surgical faculty and trainees | Only 40% correctly identified human-written abstract; 63.4% preferred the AI-generated version | Human reviewers struggle to distinguish AI texts; underscores need for transparency and guidelines |

Figure 1. Quantitative Metrics in AI vs. Human-Generated Neurosurgical Writing. This bar chart summarizes findings from four recent studies analyzing AI-generated content in neurosurgical academic writing. Metrics include Lix readability scores, percentage of accurate identification of AI-generated texts, and user preference for AI-generated content. The results highlight the consistently higher readability and significant preference for AI-written content, while also illustrating challenges in reliably detecting AI authorship. Data from Schneider et al. are partial due to lack of reported values for certain metrics.

Discussion

The findings from this review illustrate both the transformative potential and inherent limitations of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, in academic neurosurgical writing. Across the analyzed studies, AI-generated content demonstrated significantly higher readability and, in many cases, equal or greater user preference when compared to traditional human-authored texts. These results suggest that AI tools can effectively streamline the writing process, especially for tasks requiring formal structure and linguistic clarity, such as abstracts, methods sections, and technical notes.

One of the most striking observations is the difficulty experts face in distinguishing between AI- and human-authored content. In studies by Fauziah et al. and Nabata et al., reviewers correctly identified AI-generated content only 40–61% of the time—barely above chance. Furthermore, the AI-generated abstracts were preferred by a substantial portion of respondents, underscoring the persuasive power of AI in producing clear and engaging prose. These findings suggest that AI may contribute to democratizing access to academic publishing, particularly for non-native English speakers and early-career researchers who may struggle with linguistic and stylistic barriers.

However, this growing integration of AI into academic writing raises complex ethical and methodological concerns. AI tools can “hallucinate” references, fabricate plausible-sounding facts, and omit clinical nuance—shortcomings that are particularly problematic in a discipline like neurosurgery, where precision and context are paramount. The use of AI in drafting manuscripts without sufficient human oversight could compromise the quality and credibility of scientific communication.

Moreover, the studies highlight limitations in current detection methods. As shown by Schneider et al., even advanced AI-detection strategies using tools like RoBERTa combined with perplexity thresholds struggle to maintain consistency and reliability. This suggests that efforts to “police” AI usage may be less effective than developing robust policies for ethical disclosure and proper attribution of AI-generated contributions.

The current binary classification of authorship—AI-generated or human-authored—also fails to account for the reality of hybrid writing processes. Most researchers using AI do so as co-authors or assistants rather than full content generators. Thus, future research and editorial guidelines should explore more nuanced frameworks that recognize degrees of AI involvement.

Another overlooked but important benefit is the potential educational value of AI tools. When used transparently and responsibly, LLMs can serve as writing tutors for students and residents, simulate peer review processes, and assist in literature synthesis and concept clarification. Their integration into medical education could foster greater engagement with academic writing and reduce disparities in publication opportunities.

Finally, the use of readability metrics, while helpful in measuring surface-level clarity, should not be conflated with scientific rigor or depth. As some authors have cautioned, overly simplified text may compromise the precision and complexity needed for effective scholarly communication. Readability should therefore be viewed as a complement—not a substitute—for expert-driven content creation.

Conclusion

Artificial Intelligence, and specifically large language models like ChatGPT, is poised to reshape academic writing in neurosurgery. By enhancing readability, supporting non-native English speakers, and streamlining the drafting of scientific texts, AI offers practical benefits that can improve accessibility and efficiency in research communication. However, its limitations—particularly in clinical accuracy, depth of analysis, and ethical attribution—underscore the need for cautious and transparent integration.

The current evidence suggests that AI should not be viewed as a replacement for expert authorship, but rather as a complementary tool that augments human capability. Ongoing efforts must focus on establishing ethical guidelines, disclosure norms, and educational strategies that equip researchers to use AI responsibly. As technology evolves, so too must the standards of scientific publishing, ensuring that innovation enhances—rather than compromises—the integrity of neurosurgical literature.

References

1) Fauziah RR, Puspita AMI, Yuliana I, Ummah FS, Mufarochah S, Ramadhani E. Artificial intelligence in academic writing: Enhancing or replacing human expertise? J Clin Neurosci. 2025 Mar 19:111193. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111193. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40113532.

2) Schneider DM, Mishra A, Gluski J, Shah H, Ward M, Brown ED, Sciubba DM, Lo SL. Prevalence of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Text in Neurosurgical Publications: Implications for Academic Integrity and Ethical Authorship. Cureus. 2025 Feb 16;17(2):e79086. doi: 10.7759/cureus.79086. PMID: 40109787; PMCID: PMC11920854.

3) Akgun MY, Savasci M, Gunerbuyuk C, Gunara SO, Oktenoglu T, Ozer AF, Ates O. Battle of the authors: Comparing neurosurgery articles written by humans and AI. J Clin Neurosci. 2025 Feb 25;135:111152. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111152. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40010170.

4) Nabata KJ, AlShehri Y, Mashat A, Wiseman SM. Evaluating human ability to distinguish between ChatGPT-generated and original scientific abstracts. Updates Surg. 2025 Jan 24. doi: 10.1007/s13304-025-02106-3. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39853655.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming the landscape of academic writing, particularly in highly specialized fields such as neurosurgery.

Academic writing is a cornerstone of scientific advancement in neurosurgery. However, challenges such as time constraints, language barriers, and increasing publication pressure have prompted interest in AI-based writing assistants. These technologies offer opportunities to streamline research communication, support non-native English speakers, and foster collaborative knowledge generation.

AI models can process vast amounts of scientific literature rapidly, summarizing findings, identifying gaps, and aiding in systematic reviews or meta-analyses.

LLMs like ChatGPT can assist in writing abstracts, introductions, and discussion sections. While they lack domain-specific clinical judgment, they can generate well-structured academic prose that researchers refine with expert input.

AI tools correct grammar, improve clarity, and adjust the tone to align with the target journal’s requirements—especially beneficial for neurosurgeons writing in a second language.

Advanced AI platforms can suggest visualizations from datasets, organize results, and even generate descriptive legends or captions. — AI-assisted writing of case reports or technical notes (e.g., rare cranial malformations or minimally invasive approaches).

Support in drafting grant applications or ethical protocols for clinical trials.

Automating parts of conference abstract submissions and poster designs.

The use of AI raises questions about originality, credit attribution, and the integrity of the content.

LLMs may “hallucinate” or fabricate references and clinical facts if not rigorously fact-checked.

Caution is needed when inputting patient-related information into AI platforms.

AI tools can serve as tutors, helping residents and students improve academic writing skills, explore existing literature, and simulate peer review processes. — Integration with electronic health records (EHRs), improved multilingual capabilities, and the development of neurosurgery-specific AI models could further transform how scientific output is generated and shared.

AI is not a replacement for expert insight but a powerful augmentation tool. When used responsibly, it enhances the efficiency, clarity, and accessibility of academic writing in neurosurgery. Ongoing dialogue around ethics, transparency, and training will be key to its successful adoption.

Fauziah et al. discuss findings from a recent study comparing AI-generated and human-written neurosurgery articles. The study reveals that AI-generated articles exhibit higher readability scores (Lix: 35 vs. 26, Flesch-Kincaid: 10 vs. 8) but may lack depth in analysis. Evaluators could correctly identify AI authorship with 61 % accuracy, and preferences were nearly even between AI-generated (47 %) and human-written (44 %) articles. While Artificial intelligence improves accessibility and efficiency in academic writing, its limitations in clinical experience, originality, and nuanced analysis highlight the need for human oversight. The integration of AI should be as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for human expertise. Future research should focus on refining AI's analytical capabilities and ensuring ethical use in scientific publishing 1)

This letter provides a concise summary of a comparative study examining AI-generated versus human-written neurosurgery articles. While the findings offer intriguing insights into the potential and pitfalls of AI in academic publishing, the discussion raises several points that warrant deeper examination.

The use of readability scores such as Lix (35 vs. 26) and Flesch-Kincaid (10 vs. 8) provides objective evidence that AI-generated texts may be more accessible to a broader readership. This suggests that AI could serve as a powerful tool for democratizing scientific knowledge, especially in highly specialized fields like neurosurgery.

The fact that evaluators could only correctly identify AI authorship 61% of the time and showed nearly equal preference (47% AI vs. 44% human) underscores AI's potential to match human quality in terms of surface-level presentation and clarity. This is a striking finding that challenges preconceived notions about the superiority of human academic writing.

The letter wisely acknowledges that AI lacks clinical experience, originality, and nuanced judgment—essential ingredients in high-quality scientific writing. By positioning AI as a complementary tool rather than a replacement, the authors adopt a pragmatic and responsible stance.

While the letter mentions that AI-generated texts may “lack depth in analysis,” it does not provide specific examples or criteria used to assess depth or originality. These concepts are central to scientific writing, especially in a field as complex as neurosurgery. Future iterations of this discussion would benefit from clearly defining these qualitative dimensions and illustrating how AI falls short.

The accuracy rate of identifying AI authorship (61%) is interesting, but without details on who the evaluators were (e.g., lay readers vs. neurosurgical experts), it's difficult to interpret the significance of this result. The ability to discern AI authorship might vary significantly based on the evaluator’s background, and this contextual factor should be acknowledged.

The letter concludes with a call for ethical use but does not elaborate on what ethical challenges are most pressing—plagiarism, authorship attribution, misinformation, or dependency on AI? A more rigorous engagement with these concerns would enhance the practical relevance of the letter.

While AI’s role in increasing accessibility is emphasized, the assumption that readability equates to better understanding or quality may be simplistic. Readability tools favor shorter sentences and simpler words, but in scientific contexts, this may strip away necessary complexity and precision.

This letter succeeds in sparking a critical conversation about the evolving role of AI in academic neurosurgery publishing. It rightly positions AI as a promising aid but not a substitute for expert human judgment. However, to contribute meaningfully to the discourse, future works should go beyond surface metrics and delve into the qualitative dimensions that distinguish truly impactful scientific writing. Further, a more nuanced exploration of ethical and epistemological concerns will be necessary to guide the responsible integration of AI into academic workflows.

Schneider et al. analyzed 100 randomly selected manuscripts published between 2023 and 2024 in high-impact neurosurgery journals using a two-tiered approach to identify potential AI-generated text. The text was classified as AI-generated if both robustly optimized bidirectional encoder representations from transformers pretraining approach (RoBERTa)-based AI classification tool yielded a positive classification and the text's perplexity score was less than 100. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess differences in the prevalence of AI-generated text across various manuscript sections, topics, and types. To eliminate bias introduced by the more structured nature of abstracts, a subgroup analysis was conducted that excluded abstracts as well.

Approximately one in five (20%) manuscripts contained sections flagged as AI-generated. Abstracts and methods sections were disproportionately identified. After excluding abstracts, the association between section type and AI-generated content was no longer statistically significant.

The findings highlight both the increasing integration of AI in manuscript preparation and a critical challenge in academic publishing as AI language models become increasingly sophisticated and traditional detection methods become less reliable. This suggests the need to shift focus from detection to transparency, emphasizing the development of clear disclosure policies and ethical guidelines for AI use in academic writing 2).

Schneider et al. present a timely and thought-provoking investigation into the presence of AI-generated content in contemporary neurosurgical literature. Using a two-tiered detection strategy—combining a RoBERTa-based classifier and a perplexity threshold—the authors analyzed 100 randomly selected manuscripts from high-impact journals, offering insights into the subtle but growing role of generative AI in academic publishing.

The study addresses an increasingly pressing issue as large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, become more integrated into the research writing workflow. The neurosurgical community, like many academic domains, is grappling with the ethical and methodological implications of AI-assisted authorship, making this analysis especially relevant.

The two-tiered approach—requiring both a positive classification from a RoBERTa-based model and a low perplexity score (<100)—adds robustness to the AI detection method. This dual-filter method likely reduces false positives compared to reliance on a single metric.

Recognizing that abstracts are inherently more structured and possibly more prone to misclassification, the authors smartly conducted a secondary analysis excluding abstracts. This enhances the credibility of their findings by demonstrating that observed patterns are not merely artifacts of section formatting.

Rather than sensationalizing the detection of AI-generated text, the authors offer a balanced perspective—advocating for transparency and ethical guidelines rather than punitive measures or unreliable detection attempts.

While a perplexity threshold of <100 is used, the justification for this specific cutoff is not discussed. The optimal perplexity level for classifying AI-generated text likely varies depending on the domain, length, and complexity of the content. Without a validation dataset or comparison to human ratings, the accuracy of the threshold remains speculative.

The study does not report the sensitivity, specificity, or false positive rate of their RoBERTa classifier in this context. This lack of diagnostic performance undermines confidence in the AI detection claims—particularly when assessing nuanced academic text.

Although the manuscripts were “randomly selected,” no details are provided about journal selection, inclusion criteria, or manuscript type proportions (e.g., original research vs. reviews). These factors could influence the prevalence of AI-generated content and the generalizability of the results.

A sample of 100 manuscripts, while a reasonable starting point, limits the statistical power to detect more granular trends, such as variation across journals or specialties within neurosurgery.

The study categorizes text as either AI-generated or not, without accounting for hybrid authorship—a far more realistic scenario where humans and AI tools collaboratively produce text. This binary lens risks oversimplifying a complex and evolving authorship landscape.

The most striking takeaway is that roughly 1 in 5 neurosurgical manuscripts showed signs of AI-generated content, with the methods and abstract sections being most affected. This reflects AI’s increasing utility in assisting with formal, templated writing tasks. The subsequent loss of significance after abstract exclusion suggests that future detection efforts must account for inherent structural biases.

Perhaps more importantly, the authors correctly argue that detection is not a sustainable or reliable solution. As models evolve, the arms race between generators and detectors will only intensify. Instead, journals and academic institutions must prioritize disclosure policies, authorship guidelines, and norms around AI use—paralleling how statistical and graphical software tools are already handled in academic work.

Schneider et al. provide a meaningful contribution to the discussion around AI in academic publishing, particularly in high-stakes fields like neurosurgery. Their study highlights both the promise and pitfalls of current AI detection strategies, while wisely redirecting the conversation toward ethical integration and transparency. As AI continues to evolve, studies like this serve as critical signposts in developing responsible scholarly practices.

Akgun et al. in a study compare the quality of neurosurgery articles written by human authors and those generated by ChatGPT, an advanced AI model. The objective was to determine if AI-generated articles meet the standards of human-written academic papers.

A total of 10 neurosurgery articles, 5 written by humans and 5 by ChatGPT, were evaluated by a panel of blinded experts. The assessment parameters included overall impression, readability, criteria satisfaction, and degree of detail. Additionally, readability scores were calculated using the Lix score and the Flesch-Kincaid grade level. Preference and identification tests were also conducted to determine if experts could distinguish between the two types of articles.

The study found no significant differences in the overall quality parameters between human-written and ChatGPT-generated articles. Readability scores were higher for ChatGPT articles (Lix score: 35 vs. 26, Flesch-Kincaid grade level: 10 vs. 8). Experts correctly identified the authorship of the articles 61% of the time, with preferences almost evenly split (47% preferred CHATGPT, 44% preferred human, and 9% had no preference). The most statistically significant result was the higher readability scores of CHATGPT-generated articles, indicating that AI can produce more readable content than human authors.

ChatGPT is capable of generating neurosurgery articles that are comparable in quality to those written by humans. The higher readability scores of AI-generated articles suggest that ChatGPT can enhance the accessibility of scientific literature. This study supports the potential integration of AI in academic writing, offering a valuable tool for researchers and medical professionals 3).

The study by Akgun et al. offers a timely and relevant investigation into the emerging role of AI in academic publishing, particularly in the field of neurosurgery, where precision, clarity, and scientific rigor are essential. By comparing articles generated by ChatGPT, an advanced large language model, to those written by human authors, the authors sought to evaluate whether AI can meet the standards traditionally upheld in scientific literature.

The use of blinded expert reviewers minimizes bias and strengthens the validity of the comparative assessment.

Assessing not only *overall impression* and *degree of detail*, but also *readability* and *criteria satisfaction*, provides a well-rounded framework to analyze article quality.

The inclusion of both Lix score and Flesch-Kincaid grade level provides quantifiable data supporting the claim that AI-generated content is more readable.

Comparing full-length articles mimics a real-world scenario, rather than isolated paragraphs or abstracts, which adds practical relevance.

Although small, the sample included a balanced number of human and AI-authored articles. The evenly split preferences among experts suggest that ChatGPT can at least approximate human-level quality convincingly.

—

The study only includes 10 articles—five from each group. This small number reduces statistical power and limits the generalizability of the findings.

It’s unclear whether both AI and human authors were assigned comparable topics or if topic complexity varied. This could influence the evaluation of detail and readability.

The study does not specify the number, background, or specialization of the blinded reviewers. Neurosurgery is a highly specialized field, and small differences in expertise among reviewers may affect their ability to discern subtle content deficiencies.

While readability scores were higher for AI-generated texts, the degree of depth or original insight—especially in discussion sections—was not dissected. Readability does not equate to academic rigor.

While above random guessing, a 61% detection rate suggests that some stylistic cues still differentiate human from AI writing. Future studies should explore what aspects make AI texts recognizable and whether these differences are material or cosmetic.

Perhaps the most glaring omission is the lack of fact-checking or reference validation. AI can generate plausible-sounding but incorrect or hallucinated information, which can be dangerous in a clinical field like neurosurgery.

The study’s most impactful result is the superior readability of AI-generated content. This has major implications for enhancing accessibility of complex scientific literature, potentially aiding early-career professionals, non-native English speakers, and interdisciplinary researchers.

However, the finding that overall quality was comparable must be tempered by the limitations discussed. Readability and surface-level coherence do not necessarily reflect scientific originality, methodological soundness, or clinical insight—areas where human expertise remains irreplaceable.

Akgun et al.’s study is a valuable early contribution to the ongoing discussion on the role of AI in scientific authorship. It convincingly shows that ChatGPT can mimic the stylistic and structural conventions of academic writing in neurosurgery. However, further research with larger samples, broader topic coverage, and more rigorous factual verification is needed before considering widespread adoption of AI-generated content in clinical literature.

AI may not replace human authors, but it can complement them—as a tool to enhance clarity, generate drafts, or improve the accessibility of complex texts. Used wisely, this technology may democratize knowledge, but its limits must be clearly understood and ethically managed.

Nabata et al. in a study aim to analyze the accuracy of human reviewers in identifying scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT compared to the original abstracts. Participants completed an online survey presenting two research abstracts: one generated by ChatGPT and one original abstract. They had to identify which abstract was generated by AI and provide feedback on their preference and perceptions of AI technology in academic writing. This observational cross-sectional study involved surgical trainees and faculty at the University of British Columbia. The survey was distributed to all surgeons and trainees affiliated with the University of British Columbia, which includes general surgery, orthopedic surgery, thoracic surgery, plastic surgery, cardiovascular surgery, vascular surgery, neurosurgery, urology, otolaryngology, pediatric surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. A total of 41 participants completed the survey. 41 participants responded, comprising 10 (23.3%) surgeons. Eighteen (40.0%) participants correctly identified the original abstract. Twenty-six (63.4%) participants preferred the ChatGPT abstract (p = 0.0001). On multivariate analysis, preferring the original abstract was associated with correct identification of the original abstract [OR 7.46, 95% CI (1.78, 31.4), p = 0.006]. Results suggest that human reviewers cannot accurately distinguish between human and AI-generated abstracts, and overall, there was a trend toward a preference for AI-generated abstracts. The findings contributed to understanding the implications of AI in manuscript production, including its benefits and ethical considerations 4).

Nabata et al. conducted an observational cross-sectional study to assess whether surgical trainees and faculty could differentiate between scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT and original abstracts written by humans. The study involved 41 participants from a broad range of surgical specialties at the University of British Columbia, who were asked to read two abstracts—one AI-generated and one original—and identify which was produced by ChatGPT. Participants also provided qualitative feedback and preference ratings.

The study addresses a pressing issue in modern academic publishing: the rising use of AI tools like ChatGPT in manuscript preparation. With growing debates around AI’s role in academia, this research is both timely and necessary.

By including participants from a wide array of surgical specialties, the authors ensured that the study captures a diverse range of professional opinions and experiences, which enhances the generalizability of perceptions across medical subspecialties.

The use of multivariate analysis to explore the association between abstract preference and correct identification adds depth to the findings. The odds ratio (OR 7.46, p = 0.006) is statistically significant and shows a meaningful link between a participant’s ability to identify the original abstract and their preference for it.

The finding that only 40% of participants correctly identified the original abstract, while 63.4% preferred the AI-generated one, provides an eye-opening commentary on the evolving standards of scientific communication and the persuasive power of large language models.

With only 41 participants, including just 10 attending surgeons, the study is underpowered to make broad generalizations about the entire surgical or academic community. The limited number of respondents may introduce bias or limit external validity.

As participation was voluntary and confined to a single institution, those who responded may have stronger opinions or more familiarity with AI, potentially skewing the results.

The study does not provide examples or descriptions of the abstracts used. Without insight into the topics, writing quality, or complexity, it is difficult to interpret the basis of participants’ preferences and decisions.

Participants were forced to choose between two abstracts. This binary format may not capture the nuances of abstract quality perception or the difficulty in distinguishing subtle differences in tone, clarity, or structure.

If participants were aware that one abstract was AI-generated, this may have primed them to be skeptical or more analytical, thus introducing an element of performance bias. — The finding that most participants could not reliably distinguish AI-generated content raises significant questions about authorship, academic integrity, and the future of peer review. While ChatGPT-generated abstracts may be appealing for their clarity or structure, their use in scientific writing without transparency could blur the lines between human expertise and machine-generated text.

This study also touches on ethical concerns regarding authorship accountability and the potential for misuse of AI tools in scholarly contexts, where the appearance of credibility may mask a lack of original thought or clinical experience.

Nabata et al. present an insightful preliminary investigation into the interface between AI and academic medicine. Despite limitations in sample size and design, the study compellingly demonstrates that human reviewers struggle to identify AI-generated abstracts and often prefer them—a finding that underscores the growing sophistication of language models like ChatGPT.

Moving forward, larger-scale, multi-institutional studies are needed to confirm these results, investigate domain-specific perceptions, and explore the implications for peer review, publication ethics, and medical education. Importantly, institutions may need to develop new guidelines for AI use in academic writing to preserve scientific integrity in the era of generative language models.