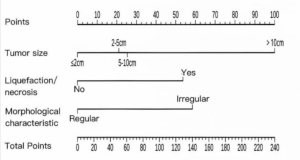

In a retrospective prognostic modeling study, He et al. from Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital published in the Academic Radiology a preoperative nomogram to identify glioblastoma patients who do not derive a survival benefit from gross total resection (GTR) compared to subtotal resection (STR), and concluded that patients with nomogram scores below 55 or above 95 gain limited survival advantage from GTR, supporting a more individualized surgical strategy 16).

🎯 Takeaway Message for Neurosurgeons

Don’t let a nomogram tell you not to operate. This study reduces complex glioblastoma surgery to a score — ignoring tumor location, function, biology, and patient context. Use it, at best, as background noise. Surgical judgment, not predictive modeling, should guide the extent of resection. Maximal safe resection remains the standard — not because of scores, but because leaving tumor behind costs lives.

1. Methodologically Weak, Statistically Dressed Up The authors claim to predict who won’t benefit from gross total resection (GTR) in glioblastoma patients — based on a retrospective model built on shaky foundations. They use multivariate Cox regression with variables like “extent of resection” to prove… that extent of resection doesn’t matter in some people. This is conceptually circular and methodologically invalid. Including the surgical outcome (EOR) in a model designed to assess the benefit of that very outcome is a self-referential fallacy disguised as analytics.

2. Nomogram Nonsense The nomogram’s seductive simplicity is its greatest flaw. It converts a deeply complex, biologically heterogeneous, and surgically nuanced disease into a scorecard illusion. Tumor location, functionally eloquent areas, MGMT methylation, TERT, EGFRvIII, and even surgical skill — all ignored. But hey, we’ve got a graph. A patient score under 55? Let’s not bother resecting that tumor — said no neurosurgeon ever.

3. Real-World Irrelevance No amount of dataset polishing (UCSF-PDGM, UPENN-GBM) can disguise the fact that surgical decisions aren’t made based on nomograms. They’re made in real time, in real patients, with real constraints. The paper assumes a clinical world that doesn’t exist — one in which glioblastoma surgeries are planned with Excel spreadsheets and cutoff scores.

4. False Authority, No Prospective Value Despite ending with a polite call for “prospective validation,” the paper’s tone implies clinical utility now. But its design cannot guide surgical decision-making, and if misinterpreted, could justify therapeutic nihilism or under-treatment in the name of statistical modeling. That’s not progress — that’s clinical cowardice wrapped in academic overconfidence.

5. Journal Fit? This is not really a radiology study. It uses imaging data, yes, but to build a weak surgical outcome model. It lives in Academic Radiology because no serious neurosurgical journal would accept a predictive tool that actively downplays surgical effort without solid mechanistic justification.

🧨 Final Verdict A dangerous mix of statistical seduction, conceptual laziness, and clinical misdirection. This paper doesn’t just miss the point of GBM surgery — it tries to redefine it with a ruler and a regression model.

🧾 File under: “Predictive modeling theater” 🔬 Useful for: Nomogram enthusiasts. 🧠 Useless for: Neurosurgeons who actually operate.